Sea turtles are highly migratory species that undertake complex migrations throughout their life cycle, posing considerable challenges for studying their behaviour and habitat use.

Most conservation efforts focus on the protection of sea turtle nesting beaches, their nests, and the nearby coastal waters (Troëng et al., 2005). However, considering that sea turtles spend most or all of their live away from nesting beaches, this approach only offers limited protection to populations as a whole.

The development of satellite telemetry in recent decades has provided important insights into sea turtle migration patterns, highlighting key migration corridors, and unlocking information on their use of breeding and foraging habitats (Broderick et al., 2007). This information is essential for effective conservation and management as one animal can traverse multiple jurisdictions, where variations in protection, environmental conditions and anthropogenic threats (e.g. bycatch, pollution, harvesting) impact the sea turtle’s longevity and survival (Godley et al., 2002).

For loggerhead turtles, foraging habitats can be located close to coastal nesting beaches or thousands of kilometres away. Foraging habitats within the Southeast Indian Ocean Regional Management Unit remain largely unstudied, except for the Eastern Gulf of Shark Bay in WA (Heithaus et al., 2005; Thomson et al., 2012). The use of satellite telemetry allows a better understanding of migratory routes and habitat use by these loggerhead turtles, which include the turtles nesting in the Gnaraloo Bay Rrookery (GBR) and Gnaraloo Cape Farquhar Rookery (GCFR) Survey Areas, and provides insight into critical aggregation areas (Godley et al., 2008), enabling targeted conservation management.

Satellite tracking of 12 post-nesting female loggerheads – 2015-2018

• Season 2017/18 – Satellite tracking of 2 female loggerheads from Gnaraloo

Two loggerhead turtles nesting in the GBR were fitted with satellite trackers in early December 2017. Both turtles, now named Gnargoo and Baiyungu, laid three more nests after the initial tagging event. Their internesting intervals shortened from 15 and 16 days to 14 days in correlation with increasing water temperatures during the internesting period, which shortens the time needed to produce a new clutch of eggs. Both turtles nested exclusively in the GBR Survey Area, but spent all internesting intervals in the waters off the beach in the GCFR Survey Area.

Where did they go?

Immediately after laying her last nest, Gnargoo started her homeward migration, which lasted approximately 3 months. She swam approximately 4,100 km before reaching her foraging habitat in the eastern Gulf of Carpentaria, approximately 35 km offshore of the remote community of Aurukun in far north western Queensland (Qld).

Baiyungu returned to her internesting habitat in the GCFR Survey Area after her last nest, and started her post-nesting migration one week later. She swam slower and less direct than Gnargoo, migrating approximately 4,700 km and taking 4.5 months to join Gnargoo in her foraging habitat.

• Season 2015/17 – Satellite tracking of 10 female loggerheads from Gnaraloo

During the sea turtle nesting seasons 2015/17, we undertook the first ever satellite tracking of loggerhead females that nest on the Gnaraloo coastline. In total, ten females from the Gnaraloo Bay Rookery and the Gnaraloo Cape Farquhar Rookery were fitted with satellite trackers during December 2015 and January 2016. Read our Satellite Tracking Report 2015/17.

Where did they go?

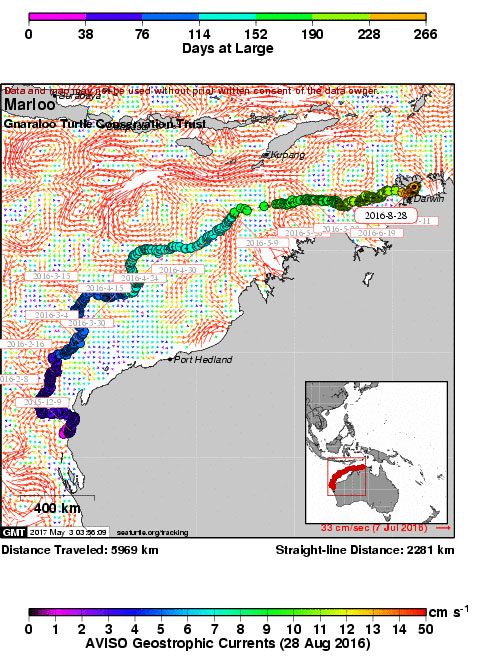

Two main migratory directions were taken. Five tracked turtles moved south to foraging grounds around Shark Bay (Western Australia). The other five turtles travelled northwards and then east, and ended their journey between Onslow and Darwin on the Australian coast (Northern Territory). All tracked sea turtles migrated great distances, between 180 and 2000 km! Nine out of the ten tracked turtles migrated along coastal waters, however, the turtle ‘Marloo’ traveled along a unique migratory track.

Marloo’s Journey – The sad end to an unusual journey for a loggerhead turtle

Aubrey Strydom (GTCP), Karen Hattingh (GWF), Dirk Slawinski (CSIRO)

In August 2016, a loggerhead turtle named Marloo washed up on Melville Island, Northern Territory. She had died from malnutrition. Her journey to the NT from Gnaraloo in Western Australia was an unusual one.

Not your normal trip

Marloo was one of ten female loggerhead turtles that were satellite tracked from Gnaraloo Bay and Gnaraloo Cape Farquhar, about 80km south of Coral Bay, by the Gnaraloo Wilderness Foundation, as part of its scientific turtle research program, which has been in place since 2008.

Her epic journey of about 5,970 kilometres which ended with her death, was not typical of the paths taken by the other four females tracked north from the two Gnaraloo turtle rookeries, who travelled close to shore when rounding the northwest corner of Western Australia at Cape Range – Exmouth on their way to their home foraging grounds where they arrived between mid February and early March 2016.

After losing more than half of her front left flipper, probably near her Gnaraloo Bay nesting beach, Marloo was taken well offshore by a local current. Now injured, and with reduced flipper propulsion during her journey, she went through two eddies which pushed her even further offshore.

Trip monitoring

The satellite tag which Marloo was equipped with has wet/dry and temperature sensors, and its repetitive signals when on the surface enable the ARGOS polar orbiting satellite system to triangulate a latitude and longitude position to within 250m.

When combining this data with the output from oceanographic models like OceanMAPS (CSIRO-BOM), we can see the likely currents which Marloo experienced during her journey. We were not sure why she was going so far offshore, but now after recovering her, we gained insight into understanding why she took a longer and wider than normal journey.

Marloo arrives too late for dinner?

Other studies have suggested that marine turtles do not eat during either leg of their nesting migration, and Marloo’s necropsy revealed no food in her crop or upper intestines, with a small amount of material including sea urchin spines in the bowel, possibly there from prior to her migration.

Three of the ten tracked Gnaraloo females had returned by the end of March 2016 to the Kimberley Coast after their migration from their nesting grounds further south at Gnaraloo. They were able to begin replenishing their body and fat reserves. Marloo’s extra four months of swimming may have meant that she was too weak to commence foraging when she arrived at the southern end of the Tiwi Islands in Beagle Bay (NT) at the end of July 2016. Her necropsy after her death a month later at the end of August 2016 found no fat left stored in her body.

The Gnaraloo Turtle Conservation Program’s satellite tracking project highlights the importance of the near shore regions along the northwest of WA, including the Kimberley Coast, as part of the foraging range of the nesting WA loggerheads, where they feed on various macro-invertebrates that thrive here, like sea cucumbers, shellfish and crustaceans.

Further reading:

Gnaraloo Bay and Gnaraloo Cape Farquhar Rookeries: Satellite Tracking Report 2015/17

Turtle Marloo’s Necropsy Report 2016/17

Marloo with her front left flipper intact on 10 December 2015 when having her satellite tracker attached. Showing the black plastic pad protecting the skin from damage by the strap buckles.

The Wildlife Computers “Spot” satellite tag that made it possible for us to follow her movements on a daily basis.

Marloo on Melville Island, 28 August 2016.

Showing Marloo’s emaciated condition 8 1⁄2 months later, and the remaining half, but healed, left front flipper stump at the start of the necropsy on 29 August 2016.

These findings offer valuable new knowledge of the foraging habitats used by some of the loggerhead turtles that nest at Gnaraloo.

The wide dispersion of foraging habitats along 4,700 km of Australia’s western and northern coastline, including 3 States and Territories, highlights the importance and necessity of comprehensive and collaborative approaches to sea turtle conservation. As sea turtles spend most of their lives in foraging grounds, protection of these habitats is crucial and directly affects the number, health and ability to migrate and breed of resident sea turtles. For effective sea turtle conservation, it is therefore not enough to focus all protection and management actions on nesting habitats.

Watch The Mystery of the Gnaraloo sea turtles

This breakthrough documentary was made at Gnaraloo about the Gnaraloo Turtle Conservation Program and the first ever satellite tracking of loggerhead females that nest on the Gnaraloo coastline. You can watch it here for free! Please consider making a donation to support our conservation efforts and help us to continue to protect the Gnaraloo nesting beaches. Thanks for watching!

References

Balazs, H. G. (1999). Factors to consider in the tagging of sea turtles. Research and Management Techniques for the Conservation of Sea Turtles. In K. L. Eckert, K. A. Bjorndal, F. A. Abreu-Grobois and M Donnelly (Eds.), Research and management techniques for the conservation of sea turtles. IUCN/SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group Publication No. 4 (1999).

Broderick, A. C., Coyne, M. S., Fuller, W. J., Glen, F., Godley, B. J. (2007). Fidelity and over-wintering of sea turtles. Proc. R. Soc. B (2007) 274, 1533-1538.

Godley, B.J., Richardson, S., Broderick, A.C., Coyne, M.S., Glen, F., Hays, G.C. (2002). Long-term satellite telemetry of the movements and habitat utilisation by green turtles in the Mediterranean. Ecography. Volume 25: pp 352–362.

Godley, B.J., Blumenthal, J.M., Broderick, A.C., Coyne, M.S., Godfrey, M.H., Hawkes, L.A., Witt, M.J. (2008). Satellite tracking of sea turtles: Where have we been and where do we go next? Endangered Species Research. Volume 4: pp 3-22.

Heithaus, M.R., Frid, A., Wirsing, A.J., Bejder, L., and Dill, L.M. (2005). Biology of sea turtles under risk from tiger sharks at a foraging ground. Marine Ecology Progress Series. Volume 288: pp 285-294.

Thomson, J.A., Heithaus, M.R., Burkholder, D.A., Vaudo, J.J., Wirsing, A.J., and Dill, L.M. (2012). Site specialists, diet generalists? Isotopic variation, site fidelity, and foraging by loggerhead turtles in Shark Bay, Western Australia. Marine Ecology Progress Series. Volume 453: pp 213-226.

Troëng, S., Evans, D. R., Harrison, E. & Lagueux, C. J. (2005). Migration of green turtles Chelonia mydas from Tortuguero, Costa Rica. Mar. Biol. 148, 435–447.

Wallace, N.J., Resendiz, A. and Seminoff, J., Resendiz, B. (2000). Transpacific Migration of a Loggerhead Turtle Monitored by Satellite Telemetry. Bulletin of Marine Science. Volume 67, issue 3: pp 937-947.

Continue reading

Sea turtle conservation

The scientific Gnaraloo Turtle Conservation Program identifies, monitors and protects nesting rookeries of endangered sea turtles on Gnaraloo beaches.

Scientific reports

Our rigorously researched documents reflect important baseline data on the sea turtles of Gnaraloo and their critical coastal nesting habitat.